Superfamily Unionacea

|

Unionacean mussels - Systematic Overview Superfamily Unionacea |

Pond mussel or duck mussel (Anodonta anatina). Pictures: © Alexander Mrkvicka, Vienna (mrkvicka.at). |

|

Inhalant and exhalant siphon of a large pond mussel (swan mussel) (Anodonta cygnea) buried in the lake floor. |

The largest freshwater mussels from the superfamily of Unionacea live on and in the floor of rivers and ponds where they feed, as their sea-living relatives do, on plankton filtered from the water they breathe. By filtering water mussels play an important role in their home water's ecology. By filtering matter from the water and by adding indigestible matter to the river's or lake's sediment, for example a pond mussel may filter 40 litres of water per day.

Systematics

Systematically the Central European River Mussels (Unionacea) are subdivided into two families: Fresh water pearl mussels (Margaritiferidae) and river mussels (Unionidae). Among the latter there are two subfamilies, namely river mussels (Unioninae) and pond mussels (Anodontinae), each with several genera and species.

Mussel Life

While the fresh water pearl mussel (Margaritifera margaritifera) and the river mussel (Unio crassus) are characteristic inhabitants of fast flowing waters like creeks and rivers' upper reaches, demanding a great deal of water quality and oxygen content (which means both species are almost extinct today), other mussel species are found in slowly flowing waters like rivers' lower reaches: Painter's mussel (Unio pictorum) and compressed river mussel (Pseudanodonta complanata). Finally inhabitants of standing water bodies, like lakes and ponds, are the pond mussels: Swan mussel (Anodonta cygnea) and duck mussel (Anodonta anatina).

Compared to the sea, continental water bodies are very unstable concerning water temperature, dryness, content of oxygen and nutrients.

Zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) also grow on other bi- valves. Here it is a river mussel (Unio crassus). Picture: © Alexander Mrkvicka, Vienna (mrkvicka.at). |

Mussels only managed to adapt to life in fresh water by developing methods to endure times of bad living conditions, such as their pond drying out. Pond mussels (Anodonta) manage to endure falling dry for up to two month, when they are dug into the ground. The can move over the pond floor by using their foot as anchor and pulling behind their cumbersome shell. On a small scale they can so move towards more favourable living conditions.

Living conditions so changeable, geographical isolation more easily led to the evolution of new species in fresh water than in the sea. For example, part of a pond falling dry could isolate one population from another, thus in the long hand leading to the evolution of a new species.

Potentially fresh water mussels can reach the largest life span in all animals. A fresh water pearl mussel for example may reach 150 years of age. Alas, in Europe only very few mussels manage to reach such a biblical age. Favourable living conditions for fresh water pearl mussels, besides small areas in Bavaria, Bohemia and Lower Austria, are only left to be found in remote areas of Scandinavia and Northern Russia. Only here, industry and agriculture have not yet destroyed rivers and creeks to an extent to make them unsuitable living grounds for fresh water mussels.

Development

|

Inside the class of bivalves the Unionaceans are a very highly developed group. The differ from sea-living mussels by a larval development better adapted to the ever changing life in fresh waters. River and pond mussels do not develop past a floating stage of planktontic larvae. Instead the large fresh water mussels develop passing a unique stage of parasitic larvae called glochidia.

A thick shelled river mussel's (Unio crassus) glochidia in a minnow's gills (Phoxinus phoxi- nus). Picture: Susanne Hochwald [1]. |

In mating time, usually approaching the end of summer, egg cells from the ovaries of the female mussel are moved into the leaf-like gills. Meanwhile the male releases sperm cells into the surrounding water, which are then taken in by the female through the inward respiration opening. In the gills, they fertilise the egg cells. It is also there that the larvae develop from the fertilised eggs. The female mussel then releases the glochida into the surrounding water .

Further development of the glochidia to become young mussels is only possible after a successful infection of a passing fish. The fishes' movement whirls up the glochidia from the ground, which now manage to attach themselves to the fishes' gills. Only a very small percentage of glochidia (a female mussel produces up to 4 million glochidia) manages to encounter a suitable fish. A far lesser percentage even manages to attach itself to the fishes' gills without being repelled by the fishes' immune system.

Some fresh water mussel species, such as the fresh water pearl mussel, are very specific about which fish species are needed for successful glochidia development, others are able to infect different species without difference.

From the glochidia then finally young mussels hatch and leave the fishes' gills. They try to settle down wherever the fish has distributed them. Infecting a fish is thus also a method of spreading the species over a large area. Until the mussel finally reaches the age of maturity, many decades may still pass.

Threats

Today in waters easily accessible to man, almost no mussels are found any more. Among the causes are anthropogenous factors (caused by man), like Eutrophication by excessive fertilising, inflow of wastes, decrease of oxygen content opposed to increase of nitrates, resulting in a decrease of fertility. A thick shelled river mussel (Unio crassus) for example will only become fertile, if the water's nitrate content remains below 10 mg/l.

A further problem is the acidification of the water because of acid rain. That has especially often severe consequences for mussel species in primarily alkaline waters, such as silicate creeks on igneous rocks such as granite.

In addition to the increasing water pollution man also changes rivers to better suit him. Rivers are dug out deeper, regulated and overbuilt with concrete structures. Mussels are impaired as well as the fish they development depends on.

Muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus). Picture: Leonard Lee Rue. |

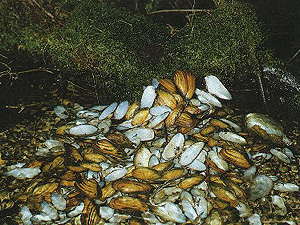

A muskrat's feeding place in winter. Source: [2]. |

Overbuilding of water flows also destroys local mussel popula- tions, as well as the fish species they depend on. Source: [2] |

A biological enemy for example is the muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus) introduced from Northern America. Basically a herbivore, the muskrat will resort to river mussels as food when food supply becomes insufficient in winter, mussels also becoming more easily accessible due to decreasing water levels.

Bitterling and pond mussel. Source: Martin Reichard. |

Another threat to fresh water mussels is, of all things, another species of mussel, that, as well, has been introduced, albeit involuntarily, by man. The zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha), because of its high speed of distribution also called wandering mussel, not only overgrows stones and rocks, but also living things, such as river crayfish and larger mussels, starving them out by food competition, as well as suffocating them by slowly burying them in the ground.

Industry's and agriculture's influence has put all Central European river and pond mussels on the red lists of endangered species in states and countries. Very demanding mussel species such as the fresh water pearl mussel, must be assumed extinct in most waters they lived in, hundreds of thousands in number, only a century ago.

On the other hand there are animals, that depend on a fresh water mussel for their development. The bitterling (Rhodeus sericeus amarus), for example, is a small carp-like fish that has to find a large fresh water mussel, a painter's mussel for example, or a duck mussel, to lay its eggs within. The young bitterlings' development then can take place in the relative protection of the mussel shell.

![]() The fresh

water pearl mussel (Margaritifera

margaritifera).

The fresh

water pearl mussel (Margaritifera

margaritifera).

![]() Threats

and protection of Austrian river mussels.

Threats

and protection of Austrian river mussels.

Additional Information (in German):